Do Your Pellets Pack Enough Punch? Field Testing from Pizza Port Carlsbad

Do Your Pellets Pack Enough Punch? Field Testing from Pizza Port CarlsbadI dropped by Pizza Port in Carlsbad, California this week to conduct a little impromptu field research with award-winning master brewer Jeff Bagby. The mission: compare Indie Hops’ type 90 pellets with that of the competition.

As reported, we’ve designed a state of the art pellet mill that’s sized and scaled to meet the needs of craft brewers. We’ve increased the average particle size of the grist and lowered the temperature at the pellet die in order to minimize damage to the lupulin glans, home of the rich and aromatic hop oils. We designed the mill with the goal of converting the form of the noble flower without excessively oxidizing the oils.

Pizza Port is near and dear to me. My wife and I have coached our kids for many years in basketball and soccer, respectively, and we wouldn’t think of holding our team “banquet” anywhere but their brewpub in San Clemente. The adults get to drink great craft beer (including outrageously awesome guest taps) and the kids get to run amok with all the root beer they can guzzle

At the 2009 GABF, Jeff won an amazing seven medals and Pizza Port Carlsbad was awarded the Large Brewpub and Large Brewpub Brewer of the Year. Not only does Jeff have the accolades, he’s also an incredibly polite, humble and decent guy who clearly loves his work.

Despite being pulled in about 12 different directions on a typically helter skelter brewing day, Jeff was kind enough to help me conduct a “field experiment” of sorts. I brought with me ice cold samples of our 2009 harvest, Oregon-grown Centennial an

d Liberty pellets. From Pizza Port’s cold storage, Jeff scooped up a jarful of pellets from the same harvest and variety, both from another supplier.

d Liberty pellets. From Pizza Port’s cold storage, Jeff scooped up a jarful of pellets from the same harvest and variety, both from another supplier.And thus began the adventure.

Does Size Matter?

The first noticeable difference was the diameter of the respective pellets. Our pellet diameter was ¼ inch; the other’s was 1/8. When we opted for a bigger diameter, our theory was that the less grist exposed to heat during pelleting, the less oxidation of volatile oils. As we’ve come to learn, the bigger the better.

Jeff broke up the pellets. IH’s pellet, he noticed, had a gummier, oilier feel and did not deconstruct into a fine powder. After concentrated finger work, the pellet broke up into small clumps. The other pellet was a tad harder, and the grind was far finer.

The Verdict: “The IH pellet feels stickier, gummier, and fresher. You can feel the oiliness.”

The Solution Dilution

Jeff then weighed out equal amounts of the respective hops and dumped them into pints of hot water. Both broke apart and dispersed at about the same rate. The IH pellets seemed to be more buoyant. They behaved, as Jeff observed, more like leafs from a flower, suspending longer and floating at the top. After a few minutes of settling, the other hop appeared to increase its density at the bottom of the pint a little more rapidly.

The Verdict: “The IH hop tends to resemble a whole flower when it hits the hot water. It’s a bit more buoyant, and there’s less water separation.”

The Exploding Flower Factor

The density of the hop-shake was substantially different. IH’s pellets blossomed into a thicker solution that resembled a creamy-clumpy milkshake. You could literally float a quarter on top of the IH “shake.” The other’s hop solution was thinner.

I had heard that the original sizing of the particles and circumference of the pellet was driven by the notion that a thinner solution would be easier to wash down the drain after the wort was sent to the heat exchanger. Jeff theorized that the thickness of the IH hops would not pose any sort of clogging problem. “We drain our hop residue into the public sewer system, which I’m sure can easily accommodate a coarser hop grind.”

The Verdict: “The Indie Hops pellets were like a thick Texas chili; the other was more like pea soup.”

What about the aroma?

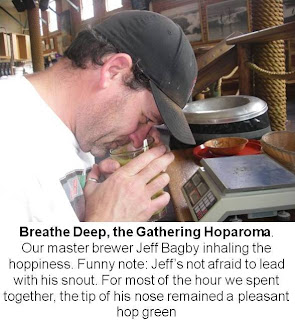

Finally, the aroma. First, a disclosure. Jeff has been a brewer for over 10 years and he has been using The Other Guy’s Centennial pellets for at least that long. He is accustomed its aroma and uses their pellets in his award-winning Shark Bite, a hopped up IPA which is the beer I usually order when I bring my family to Pizza Port up the road in San Clemente. The point: Jeff is both accustomed to this hop and obviously satisfied with it.

Now then. Jeff noted that The Other Guy’s Centennial hop brew exuded a “sharp, skunkier, marijuana aroma.” The IH pellet, brew by comparison, had a “more herbal, spicy, peppery” aroma.

The Verdict: “I was amazed at the difference in aromas. Each had a distinct aroma, both nice, but the [Indie Hops brew] smelled fresher, greener. It’s incredible when you think they are the same variety harvested the same year.”

Pizza Port’s supplier of the hop in question was from Washington, but we don’t know where the hops were grown. Nor do we know exactly who pelleted said hops. The IH hops were grown on Goschie Farms in the Willamette Valley, Oregon. They were pelleted about 2 months ago at our new “patient” pelleting mill in Hubbard, Oregon, located only a few miles up the road from Goschie Farms.

Thanks Jeff, we appreciate your candid feedback. Throughout the session, I nursed a pint of Sharkbite, which featured the Other Guy’s hops. I loved it. It’s hard to imagine improving an already delightful taste, but like my partner Jim says, “The day you stop getting better is the day you start getting worse.” At Indie Hops, we aim to get it right. Brewer feedback is not only essential, it’s fun. It’s even more fun when it validates our theories about the linkage between pellet particle size, pellet surface area to volume , and pellet die temperature.

As another well respected brewer in nearby San Marcos, Tomme Arthur of Lost Abbey, recently suggested to me: if less oxidation is the Holy Grail, why not process cigar sized or even hockey puck sized pellets? Good question. We’re on it!